Just recently, Yuga Labs, the team behind the world-famous bored nonfungible token (NFT) primates, nabbed some $300 million with its sale of Otherdeed NFTs, a collection of land plots in a soon-to-be metaverse. Indeed, NFTs, the blockchain industry’s primary method of creating digital asset scarcity, have emerged as the preferred way to handle virtual land ownership for most metaverse projects, including Decentraland and The Sandbox. All of this has prompted an interesting question in the community: In the metaverse, a vast, near-endless digital space, how can digital land ever be scarce? Well, let’s dig in.

First and foremost, let’s address the elephant in the room: The metaverse isn’t real. I mean, the Ready Player One-style metaverse, a seamless virtual reality-based rendition of the internet as we know it. So, while you may don your VR helmet for a rave in Decentraland, the device will hardly stay on for your daily dose of Instagram or a news feed surf.

In other words, what we have right now is a growing number of relatively siloed metaverse projects, which offer users an array of project-specific experiences and functions as opposed to the browse-whatever of the larger web. This in itself hints that scarcity is a valid concept to consider in as much as their lands go, even if we consider their value through the same prism as real-world land.

Related: Sci-fi or blockchain reality? The ‘Ready Player One’ Oasis can be built

The laws of the land

In the real world, the value of a plot of land is a product of a few quite clear-cut variables — i.e., natural resources, from oil or mineral deposits to forestry and renewables, access to infrastructure, urban and logistical centers, and fertile soil. All of this can come into play depending on what you are planning to do with this land. Purpose defines value, but the value is still quantifiable.

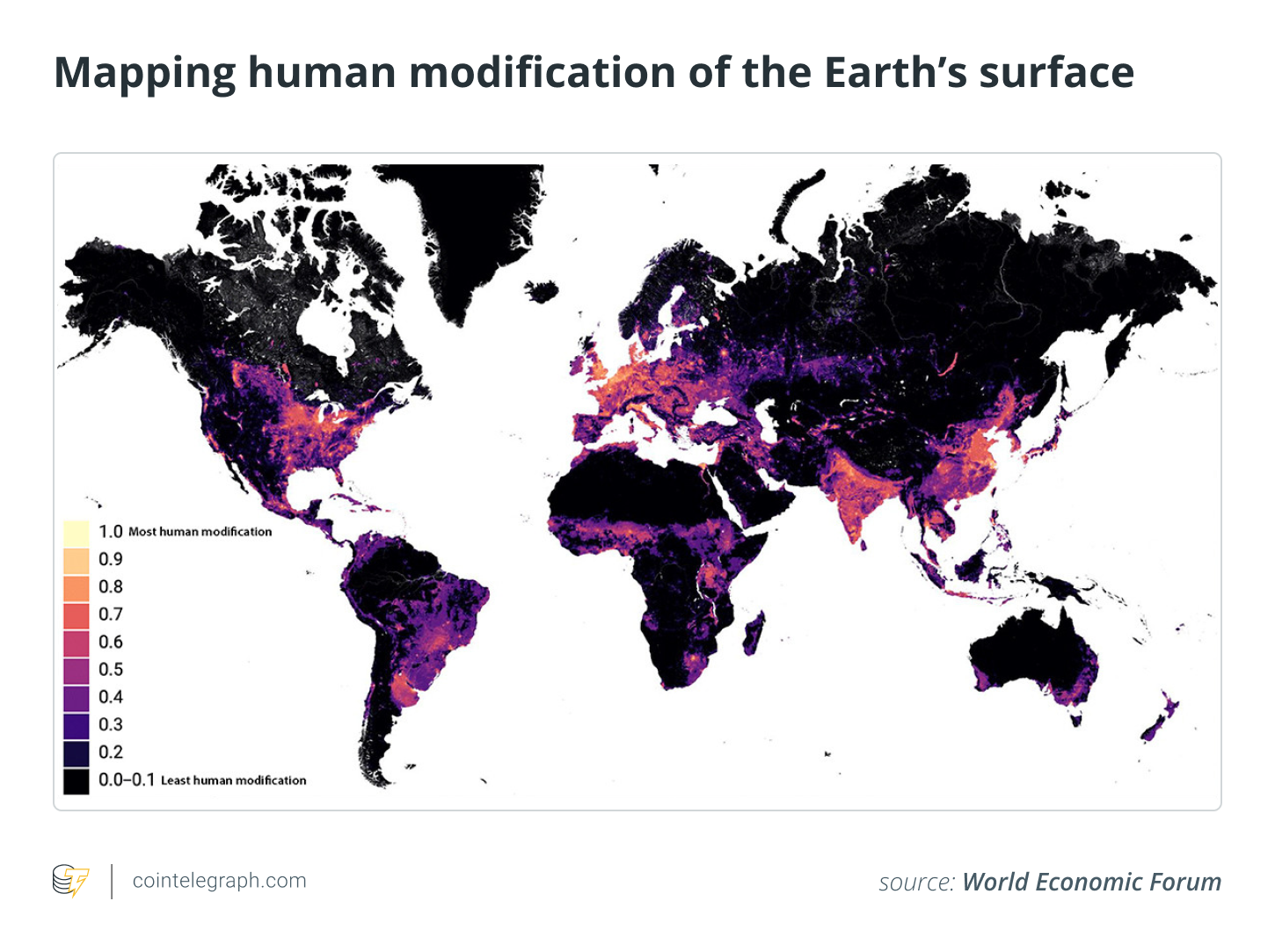

Value, for its part, often goes hand in hand with scarcity, and land is no exception. The planet’s total surface area is 510.1 million square km, but more than half of that is under water, which works for oil and gas pipelines and submarine cable lines, but little else. So far, we have modified about 15% of the available land area, and yet, at the end of the day, land is finite. Factor in the value and financial feasibility considerations (an investment has to be worth it), and the pool of land that actually makes sense to acquire goes even slimmer.

Let’s take The Sandbox as an example. What’s the value of getting there? Again, value comes from purpose. If you are a fashion brand, for example, you would probably benefit from being in a similar digital space as Gucci. What’s more, if you are looking to compete with this brand, you would want your plot located as close to its own as possible to try and cut into its footfall with the stunning exterior of your own outlet.

Related: The metaverse is booming, bringing revolution to real estate

This is where scarcity comes back into play. There are only so many NFT plots that you can buy next to the Gucci store. In a digital realm, distance as such may seem arbitrary, but it’s not entirely correct. Distance comes down to how this specific metaverse handles space, objects and movement — the crucial, foundational components of its design. After all, you probably want your own metaverse store to be an actual 3D store a buyer can explore, which demands a 3D spatial grid and at least a basic physics engine. Sure, it’s probably possible to play with non-Euclidian geometry and other smart design features to make the space bigger on the inside than on the outside, but this would amp the workload on the backend and affect the user experience.

As we see, technological constraints and business logic dictate the fundamentals of digital realms and the activities these realms can host. The digital world may be endless, but the processing capabilities and memory on its backend servers are not. There is only so much digital space you can host and process without your server stack catching fire, and there is only so much creative leeway you can have within these ramifications while still keeping the business afloat. These frameworks create a system of coordinates informing the way its users and investors interpret value — and in the process, they create scarcity, too.

The great wide world out there

While a lot of the valuation and scarcity mechanisms come from the intrinsic features of a specific metaverse as defined by its code, the real-world considerations have just as much, if not more, weight in that. And the metaverse proliferation will hardly change them or water the scarcity down.

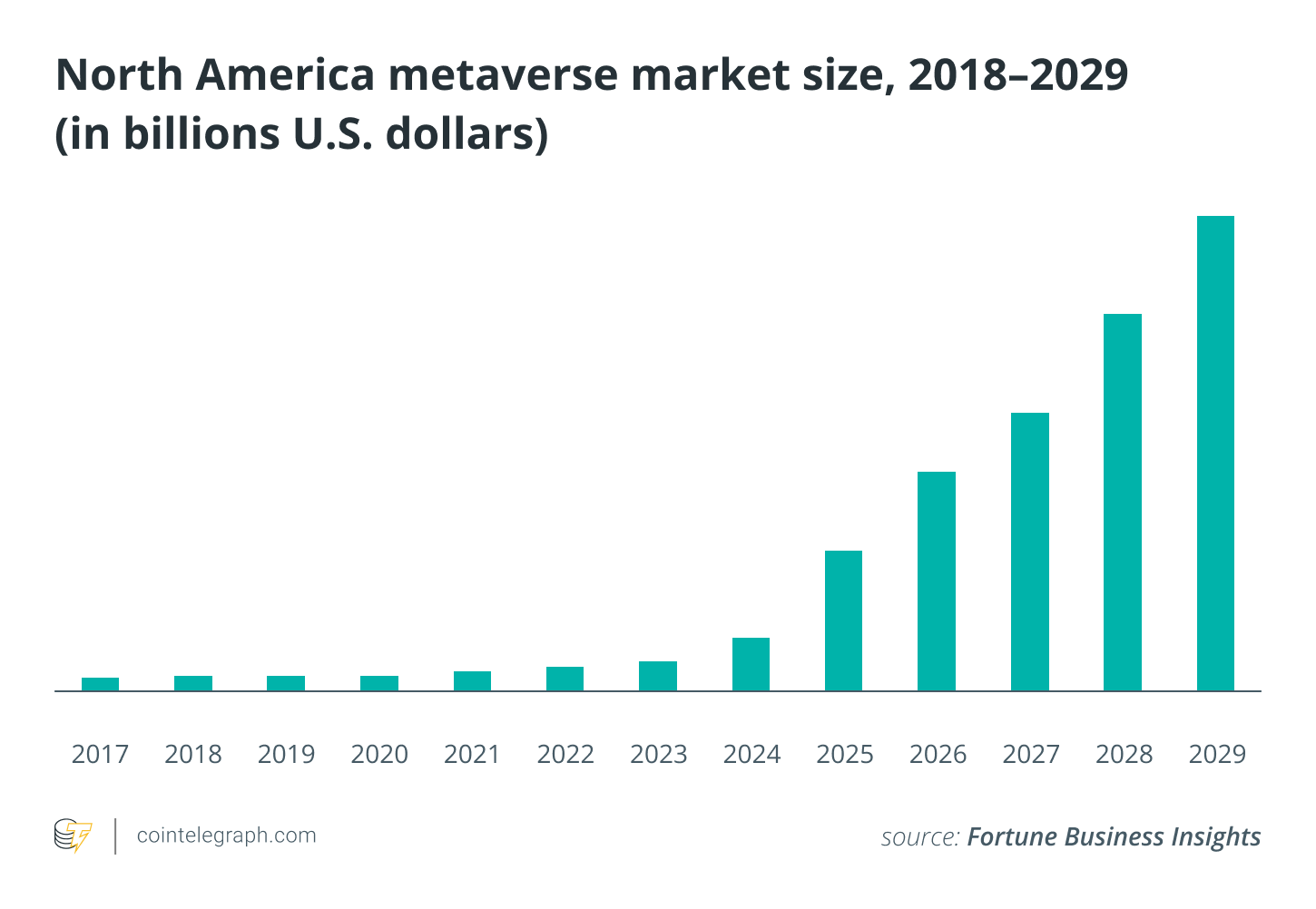

Let’s start with the user bases. The Sandbox reports 300,000 monthly active users, and for Decentraland, the figure is roughly the same. In terms of pure math, this is the cap for your monthly footfall at whatever metaverse outlet you are running. So, even if they are not too impressive, they will likely be hard to beat for most newer metaverse projects, which, again, takes a toll on the value of their land. By the same account, if you have one AAA metaverse and 10 projects with zero users, investors would go for the AAA one and its lands, as scarce as they may be. This also creates a value-driven meta-scarcity: Sure, there’s plenty of land in general terms, but only a limited portion of it makes a feasible investment.

Related: How blockchain technology might bring triple-A games to metaverses

A comparison with on-page ads will be helpful here. Advertisers prefer websites with more traffic, and the number of ad spots on a page is limited by the constraints of reasonable UX. You can always make another dozen websites, but if they don’t bring in the same traffic, the ad spots there will hardly be as valuable, and the ones on the top site are scarce.

Moving beyond the user bases, there is also the intangible wow-factor. One of the reasons why brands buy lands in metaverses is because they know the media will write about it. It’s true that the biggest companies will generate traction no matter what metaverse they would enter through their own sway. Still, they would rather roll with something that’s built up some traction on its own, in the same way they would prefer coverage on Bloomberg to a tiny newspaper. Brands like partners who play in the same league, or punch above their weight, or at least come off like they’re doing any of that. And those are usually scarce.

Related: Basic and weird: What the metaverse is like right now

One day, we may indeed end up with a single coherent metaverse, but even there, the rules binding it will likely work as a natural — or artificial — foundation for conceptualizing value, which will likely factor in scarcity in some form. Now, in a world of scattered metaverses that users cannot seamlessly bounce between, competition and, by extension, scarcity are very much part of the equation.

This article does not contain investment advice or recommendations. Every investment and trading move involves risk, and readers should conduct their own research when making a decision.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views and opinions of Cointelegraph.

Adrian Krion is the founder of the Berlin-based blockchain gaming startup Spielworks and has a background in computer science and mathematics. Having started programming at age seven, he has been successfully bridging businesses and tech for more than 15 years, currently working on projects that connect the emerging DeFi ecosystem to the gaming world.